A Teaching Revolution Is Transforming Student Learning at UBC

For most of the last century, teaching was the same. A university lecture in 1920 did not look that different from a lecture in 1980. A professor stepped up to the podium and imparted wisdom in a 45-minute monologue. Students took notes. The end.

Those days are long gone at UBC. The introduction of the Internet and the advent of personal computing have changed everything.

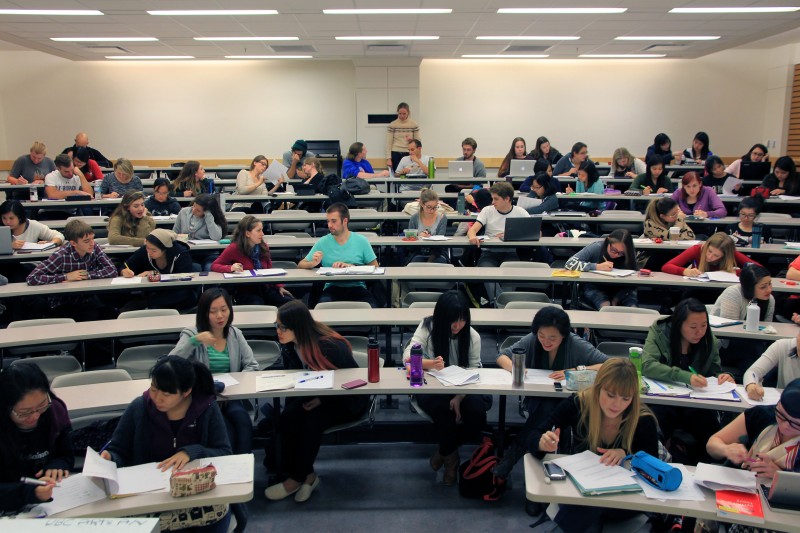

Today, when Dr. Simon Bates holds a physics session for 300 undergraduates, they arrive having read and digested all the material in advance. His role is facilitating engagement, which includes problem solving, spontaneous questions and discussion in breakout groups. It’s called a “flipped classroom” and it has changed the post-secondary learning environment at UBC and transformed the student experience.

“If you were to parachute into one of my lectures, you’d probably think I’d lost control of my class,” says Bates, Professor of Teaching in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, Academic Director of the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology, and member of the Flexible Learning Implementation Team. “It’s noisy, interactive and slightly unpredictable. I have a rough map of what I’d like to do, but I vary it. I spend time challenging understanding, highlighting connections or testing.”

According to former UBC President Stephen Toope, four factors are driving a warp-speed acceleration of learning models at UBC: a better understanding of how we learn, transformative technologies, new demands for options and the rising costs of the traditional model.

First, thanks to advances in cognitive science, we know more about how to design effective learning. For example, research has shown that testing more often teaches us to retrieve information under stress and improves long-term memory.

Then there are technological advances. Today, information is accessible anywhere, anytime. “From about age 14, we carry a device that gives us information about anything on demand,” says Bates. “By 21, people have been exposed to more information than they were in an entire lifetime a generation ago. It’s absolutely startling.”

Technology also provides untold opportunities for collaboration. Professors can continue conversations online. Undergraduates studying food security can connect with peers in other countries. Says Bates: “Technology allows you to bring the world into the classroom in a very real, tangible way that has not been possible or practical before.”

These changes have shifted the role of faculty at UBC. Rather than delivering content for the first time, professors are adding value as guides who help students navigate and evaluate the influx of information. UC Irvine Professor Alison King noticed this shift in 1993 and penned a seminal essay about it entitled “From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side” for the journal College Teaching.

The marketplace is also having an impact. Employers want staff that can identify problems and ask questions, while students want practical learning opportunities. UBC’s focus on experiential learning gives students the chance to dive into real-world problems.

UBC’s 66 years of distance learning has also helped the university educate thousands of non-traditional students, such as the 40-year-old working mom in Prince Rupert seeking advanced certification.

These are just some examples of how UBC faculty members are backing away from the lectern in order to engage students and spark critical-thinking skills that drive innovation in today’s world.